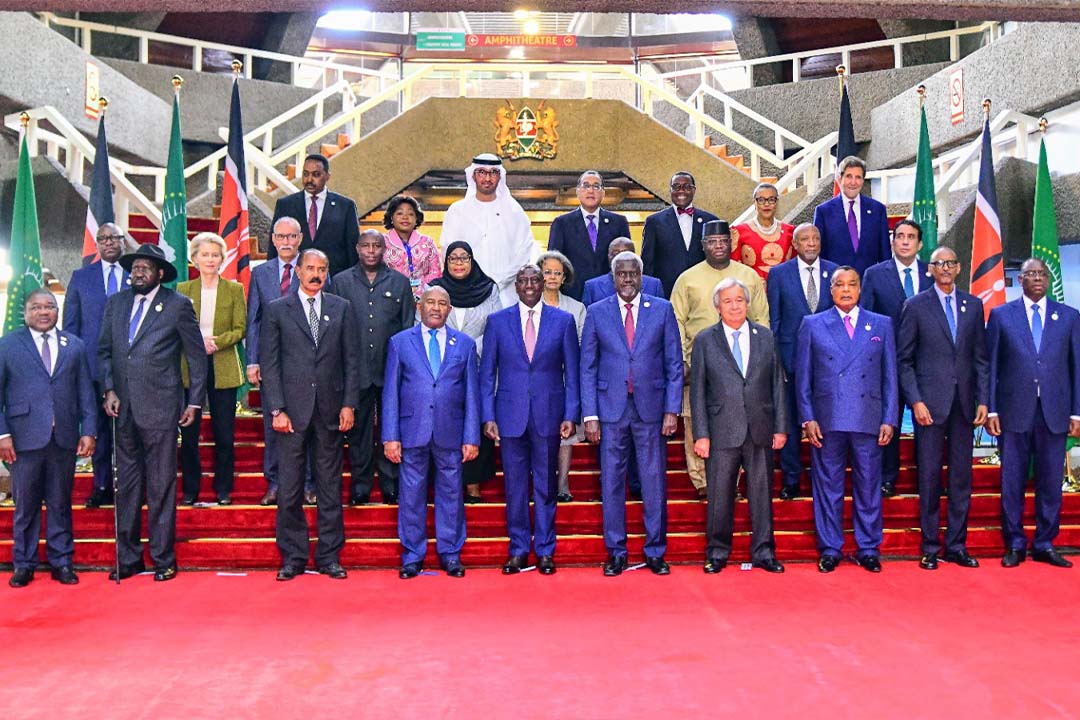

We all saw the videos and photos. In all its glory, Nairobi was furnished by electric public transport and that convoy of small battery-powered cars that President William Ruto led from his residence to the conference venue. The praises from UN Secretary-General Antonio Gutierres and EU Commission President Ursula Von Der Leyden, the oohs and aahs from members of the international press.

On surface value, The Africa Climate Summit was a great event, but beneath the surface, the messages sent during the summit indicate a more aggressive policy approach by the continent to climate matters.

The Nairobi Declaration: Digging in

The main resolution of the summit was the Nairobi Declaration. African Heads of State called for investment to promote the sustainable use of Africa’s natural assets for the continent’s transition to low-carbon development and contribution to global decarbonization.

“We call for a comprehensive and systemic response to the incipient debt crisis outside default frameworks to create the fiscal space that all developing countries need to finance development and climate action,” the declaration reads in part.

The numbers to support this argument are ominous. Africa only receives three per cent of global dollars dedicated to mitigating and adapting to climate change despite being the second most populous continent in the world and the most prone to the effects of climate change.

The financial angle is typical in these summits, but the devil is in the detail. The declaration read more like an ultimatum than a request and signalled Africa’s willingness to take up a position as a protagonist in global climate affairs rather than wait for handouts.

Host President William Ruto summed it all up by saying, “We demand a fair playing ground for our countries to access the investment needed to unlock the potential and translate it into opportunities.”

This was followed by him re-echoing a promise he made last year that by 2030, Kenya will fully be dependent on renewable energy.

Key amongst the points of discussion was how Africa emits the least carbon but suffers the effects of climate change the most with the continent being plagued by multiple climate related effects such as erratic weather patterns and drought.

Other African leaders present made profound, reaffirming statements that, from an African Union perspective delivers a new dawn.

The President of Africa Development Bank, Akinwumi Adesina noted that the continent’s GDP should be revalued for its assets, which include the world’s second-largest rainforest and biodiversity.

“It’s becoming increasingly difficult to explain to our people, particularly to our youth, the contradiction: resource-rich continent and poor people,” Ethiopian President Sahle-Work Zewde said.

Foreign influences

Several Western countries and regional blocs such as the EU and the U.S government pledged financial assistance to individual countries and the AU as a bloc, which was seen as positive by some but as an attempt to sway the outcome of the talks by others.

A case in point is U.S Special Presidential Envoy for Climate, John Kerry who is not particularly liked by Ugandan president, Yoweri Museveni who according to the Daily Nation told Kenyan officials that he would not sit and be lectured by a representative of one of the world’s biggest polluters.

On that note, It is also important to look at the glaring absences of the heads of states from Congo, Uganda, Nigeria and South Africa with all four presidents being considered key AU thought leaders. Many interpreted this as an unwillingness to associate themselves with the objectives of the conference.

Nigeria and South Africa are some of the biggest benefactors of fossil fuels with large reserves of oil and coal respectively and Uganda have been working on an oil exploration and pipeline project for the past decade. This is something that may have played a role in their absence.

The conspicuous absence of China at the talks also went unnoticed. The Asian powerhouse is a key carbon emitter and a huge trade partner for most African countries.

Conclusion

The fact that this is the first time African countries congregated to discuss climate on their own accord points to a willingness to pursue local solutions to local problems. As all eyed focus on COP 27 in Dubai in December, the main question is whether the discussions brought forth in Nairobi will be echoed in Dubai, or will we slink away below the table when the so called ‘big boys’ of the global climate discussion start talking.